Sent from my ipod

A Programmer's Recipe For Scraping The Web

There is a lot of data locked behind the websites we visit every day. What you see on a page is usually just a tiny sliver of all the information that a website hosts. Some websites expose all this data via an API, but most don’t.

What if you want data from websites that don’t provide an API? A good but inefficient way is to open different links of the website, copy the data you want, manually, into a format that you can later use for data analysis. Is there a better way to get hold of all this data without spending a ridiculous amount of time engaged in mind numbing tasks? Yes, there is. In fact, Google indexing works using a similar paradigm. This is exactly the type of task computers are good at.

Having done this a couple of times, I want to share a framework to deal with such problems using an example.

Define The Problem

This sounds very obvious, but your ability to get the right data heavily depends on this step. Write it down.

Let us pick an example in our case. I enjoy Crossfit. It has a lot of positives with a few downsides (a topic for another day) and I follow the daily workouts posted on crossfit.com. This is a website maintained by the official headquarters and they have been posting a workout a day since the year 2002. My goal is to get all the workouts posted since 2002 in the format below into a tab separated file:

Date Workout

20140519 Complete as many rounds as possible in 10 minutes of: 5 bar muscle-ups 135-lb. thrusters, 10 repsPick Your Tools

The post assumes that you know how to install the necessary tools on your machine. I will provide the necessary links to where you can find the software, but showing you how to use pip gets boring very quickly :)

There are many tools available for scraping the web but I urge you to pick tools that give you the most amount of flexibility. I automatically lean towards programming instead of out of the box tools for obvious advantages like customizability, accommodating requirement changes and reusability. Python is great at these tasks because it is, what I call, a glue language. Python has had continued interest in different domains and that allows Python interface easily between data munging, scraping, transformation, visualization and hosting web applications.

We’ll do this example in Python and use a excellent library called Beautiful Soup.

For the IDE,<ahref =”http://ipython.org/notebook.html”> IPython</a> is fantastic. The advantage of IPython is the ability to re-run segments of your code instead of the entire program, which is excellent when you are experimenting with unknown data or figuring out language capabilities. The last library we need is<ahref =”http://pandas.pydata.org/”> Pandas</a>. We technically don’t need Pandas, but it makes it easier by allowing us to transform data with the help of multi-dimensional array manipulations. It is used a lot in the scientific community and is a wrapper on top of Numpy and Scipy. If you haven’t dealt with Pandas before, I recommend you look at this quick intro from the creator, Wes McKinney or I highly recommend his book.

If you are on a Mac, you can use Chris Fonnesbeck’s install script that will download Pandas and all its dependencies. If you are on Windows, you can use the free version of the Enthought distribution install. It does a pretty good job.

I am personally not a big fan of the debugging capabilities that come with Python and I almost always rely on an IDE like PyDev or Spyder when I want to debug some code. My workflow ends up going back and forth between IPython for experimentation and PyDev for debugging. Long story short, pick tools that you are comfortable with and be flexible to switch between tools.

Discover Patterns

Now that we are all set up, on to the good stuff!

Every web page on a website has a blueprint. Think of each blueprint made of boxes of text and each of these boxes could contain one or more boxes. Our goal is to create a hierarchy of boxes we care about, programmatically using Python and Beautiful Soup.

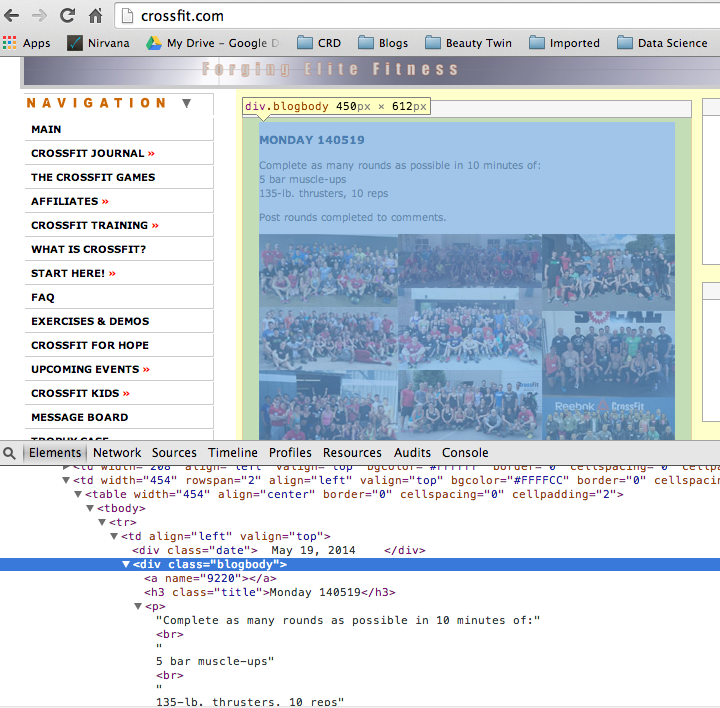

Navigate to a site like Crossfit.com. Right click on the text that we are interested in within Chrome and select inspect element. This will display the HTML rendered by the site in the developer tools, like below.

The “boxes” we care about in this document are :

- Everything within the ‘div’ element where the class is ‘blogbody’

++ The ‘h3’ element where the class name is ‘title’. This is the date the workout was posted on.

++ The ‘p’ element which is the workout description.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

from datetime import datetime

import calendar

import numpy as np

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import requests

import csv

with open("workouts.tsv", "w+") as f:

fieldnames = ("Date", "Workout")

output = csv.writer(f, delimiter="\t")

output.writerow(fieldnames)

url = "http://www.crossfit.com/"

r = requests.get(url)

soup = BeautifulSoup(r.text)

#print soup

blogBodies = soup.findAll("div", {"class" : "blogbody"})

for line in blogBodies:

#print('\n~break~\n');

workoutName = line.find("h3", {"class" : "title"})

#print workoutName

if workoutName is not None:

if(len(workoutName.text.split()) < 2):

# Some entries only have the day and not the actual date

#workoutDate = np.nan;

break;

else:

#Add 20 to the year part, so Pandas can easily extract the date format

workoutDate = "20"+workoutName.text.split()[1];

para =line.findAll('p')

workout = "";

for p in para:

# Sometime their workouts have links and they need to be filtered for

anchorExists = p.find("a")

if (p.text=='Enlarge image') |('Post' in p.text)|('comments' in p.text)|(p.text == "") :

break;

else:

workout = workout+p.text.encode('utf-8')

output.writerow([workoutDate,workout.strip().replace('\n',' ')])

OK, like with any piece of code, there seems to be a lot going on here. I promise, it’s not the case. Take a deep breath and let’s break it down :

line 8 : Open a file where we want to write our output

line 12: The URL we want to parse

line 14: Convert our site to a Beautiful Soup template that we can easily parse and query

line 16: Grab all the ‘div’ elements that have the class name as ‘blogbody’. (Remember, this was our main container)

line 19: Grab all the ‘h3’ elements that have the class name as ‘title’. (This is the workout date)

line 29: Grab all the ‘p’ elements from each line in ‘blogbodies’. (This is the workout name and description)

Ignore the other lines for now. We will tackle them in the “Dealing With Gotchas” section below, which are just special cases to get around data quirks.

Your output will look like this :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Date Workout

20140519 Complete as many rounds as possible in 10 minutes of: 5 bar muscle-ups 135-lb. thrusters, 10 reps

20140518 Rest Day

20140517 Run 1600 meters Rest 3 minutes Run 1200 meters Rest 2 minutes Run 800 meters Rest 1 minute Run 400 metersCompare to 121017.

20140516 50-40-30-20-10 reps for time of: GHD sit-ups 2-pood kettlebell swings

20140515 7 rounds of: 15 hip-back extensions 3 strict muscle-ups

20140514 Rest Day

20140513 Helton3 rounds for time of: Run 800 meters 50-lb. dumbbell squat clean, 30 reps 30 burpees

20140512 Front squat 3-3-3-3-3 reps

20140511 Complete as many rounds as possible in 20 minutes of: Run 400 meters Then 3 rounds of: 5 pull-ups 10 push-ups 15 squatsCompare to 121119.

20140510 Rest Day

The date of the workout followed by the workout description.

That’s it! The code above constructs the blueprint and we just need to repeat this process for all the URLs that we need data from, which we will look at in the next section.

Construct URLs Recursively

In our case, if we navigate to a URL like “http://www.crossfit.com/mt-archive2/YYYY_MM.html”, we will have access to all the archives. Again, it’s just about finding the pattern, like in the previous section. Once we have the pattern, write a simple method to auto-generate our URLs :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

def generateURL():

crossfitBaseUrl = 'http://www.crossfit.com/mt-archive2/YYYY_MM.html'

yearRange = range(2002, 2014)

monthRange = ['01','02','03','04','05','06','07','08','09','10','11','12']

crossfitUrls = [];

for year in yearRange:

for month in monthRange:

crossfitYearUrl = crossfitBaseUrl.replace('YYYY', str(year))

crossfitUrl = crossfitYearUrl.replace('MM', str(month))

crossfitUrls.append(crossfitUrl);

return crossfitUrls

Iteratively pass in the output from the generateURL() method to the code in the previous section and that will print workout dates and workout names to the tab separated file.

Munge Your Data

Once our data is written to the tab separated file, we can ‘clean’ rows, deal with date formats, check if we have all the data, the right data, transform or munge data as necessary.

I realize that this post has grown much larger than I intended it to be, so we’ll look at the transformation of this data using Pandas as part of another post.

For now, below is a simple way to move all our data to a DataFrame. Google up for some DataFrame tutorials and try applying some transformations. Once you get comfortable dealing with multi-dimensional arrays (which is essentially what a DataFrame is) you will find Pandas to be efficient and enjoyable.

1

2

3

4

cols =['Date','Workout']

df = pd.read_csv('workouts.tsv', sep='\t', converters={'Date': str})

df = df.dropna()

print df

Dealing With Gotchas

On to the lines we skipped above. As we encounter more example of data parsing, your biggest time sucker is programming defensively. You start to encounter so many unforeseen circumstances that it’s hard to code against every single case.

line 22: Sometimes, the ‘workoutName’ has just the weekday and doesn’t have the actual date the workout was posted

line 28: Had to manually add the “20” part of the year for Python to recognize the date as an actual date format

line 34: Not all ‘<p>’s consist of the workout description, some of them could be comments or embedded images. Just a simple way to ignore such texts

line 38: Avoid new lines and remove empty spaces from workouts

Some Broader Ideas

Following a couple of rules has helped me parse web sites more efficiently. In fact, we can apply these principles if we are hacking on any unstructured code or tiny projects:

Iterative Development

Build it - build it right - simplify it - and optionally, make it fast. Don’t worry about getting all the cases right in the first go about. Just get something down and refine to get the right data. Once you have it, simplify your code to make it modular and reusable. As we did above, start with a single URL, then try parsing the data for a month. You will encounter some unforeseen issues, fix them and try parsing the data for a couple of months and so on..

Reusability

You will deal with the same sought of problems like parsing dates, escaping unicode characters, generating URLs, reading from files, writing to files. Create a Python module and reuse the methods. The best code is the code you don’t write at all. I plan to open-source my reusable module for web parsing sometime soon after some tidying up. There is just too much stuff in one big module at this point.

Print Statements For Debugging

I don’t care what the haters say, I have found tremendous use of just printing output instead of launching the full on debugger but you should definitely look into learning a tool like Pydev( a Python plugin for Eclipse) or Spyder for some variable inspection level debugging.

Good luck and let me know if you have any questions or if I can improve this post in anyway. Happy hacking!

As always, you can find the source for this on my Github account. You can also find an IPython notebook with the code here.