There’s a default assumption baked into most AI product work: the model runs at request time. The user does something, the system calls a model, the model returns a result. It’s how we build chat features, search ranking, content generation — anything with AI in the loop.

But there’s a large class of AI-powered features where this assumption is wrong. Where the expensive computation can happen once, offline, and the live product is just arithmetic. Where you can ship a genuinely useful AI experience with zero inference cost at runtime.

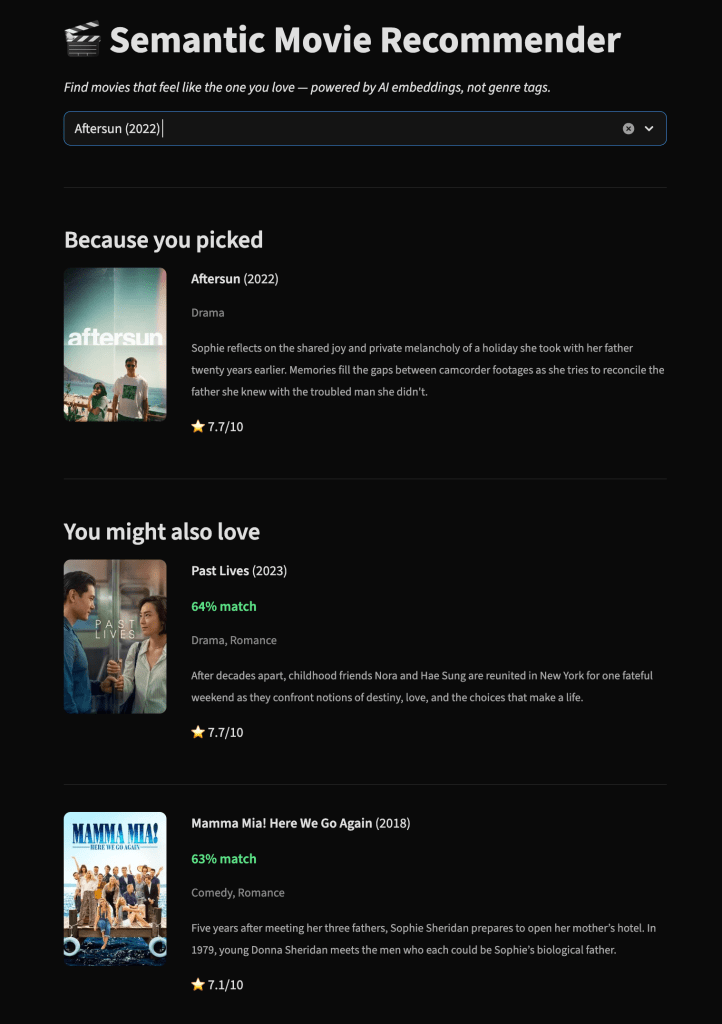

To test this idea, I built a small project: a semantic movie recommender that finds the three films most similar to any movie you pick — not by genre tags or collaborative filtering, but by the actual meaning of what each movie is about. It costs nothing to run. The project itself is simple, but the product thinking behind it is what I want to unpack.

The Pre-Computation Pattern

The core insight is this: if your dataset doesn’t change at request time, your model doesn’t need to run at request time.

Most recommendation systems, semantic search features, and content-matching tools operate over a relatively stable corpus. The movies in a catalog don’t change every second. Neither do products in an e-commerce store, articles in a knowledge base, or candidates in a talent pool. The “understanding” step — converting content into a representation the system can reason over — only needs to happen when the content changes.

For my movie recommender, that means: take ~5,000 movies from the TMDB dataset, construct a rich text representation for each one (plot, genres, director, cast, keywords), and run them through an open-source sentence transformer. Each movie becomes a 384-dimensional vector — a point in meaning-space. Store all the vectors in a FAISS index. Total time: about sixty seconds on a laptop.

At runtime, the app loads the pre-computed index and does a dot product to find the nearest neighbors. No model call. No GPU. No API. Just linear algebra over an 8MB file. FAISS returns results in under a millisecond.

The “AI” already happened. What’s running in production is math.

Why the Input Matters More Than the Model

The most interesting lesson from building this was about input engineering, not model selection.

My first attempt embedded only the plot overview for each movie. The results were fine — semantically coherent, but generic. Everything similar to Inception was just “heist movie” or “sci-fi thriller.” The recommendations were technically correct but missed the feel.

Adding the director, top cast, genres, and thematic keywords to the input text changed everything. The embedding for Inception was no longer just “a thief who steals secrets through dream technology.” It was “Sci-Fi, Action, Thriller. Directed by Christopher Nolan. Starring Leonardo DiCaprio. Keywords: dream, subconscious, heist.” That richer signal pushed the vector into a much more distinctive region of the embedding space.

The model I used — all-MiniLM-L6-v2 — is small, free, and unremarkable. It’s 80MB and runs on CPU. But it doesn’t need to be remarkable. It just needs a good input. The model is commodity infrastructure. The input construction is the product decision.

This maps directly to a pattern I see in production AI features. Teams spend enormous energy selecting and fine-tuning models while underinvesting in the data and context they feed into those models. The highest-leverage work is often upstream of the model: what signals do you include, how do you combine them, what context makes the output meaningfully better?

When This Pattern Applies (and When It Doesn’t)

Pre-computation works when three conditions hold: the corpus is relatively stable, the task is matching or retrieval rather than generation, and the query can be resolved by comparing against pre-built representations.

Recommendation systems are the obvious case. Content similarity, product matching, document deduplication, semantic search over a known corpus — these all fit. You can pre-compute embeddings for your entire catalog and serve results with nothing but vector math.

The pattern breaks when the task requires generating novel content, when the corpus changes faster than you can re-index, or when the query itself needs to be deeply understood by a model (complex multi-turn reasoning, for instance). A chatbot needs real-time inference. A movie recommender doesn’t.

The interesting middle ground is features that use pre-computation for the heavy lifting and reserve real-time inference for a thin layer on top. You could pre-compute all your document embeddings but use a small model at query time to understand the user’s intent before searching. The expensive retrieval happens offline; only the lightweight interpretation happens live.

The Product Decision

The broader question this project crystallized for me: when we scope an AI feature, are we asking where the computation should happen?

The default is to put it at request time because that’s how most AI infrastructure is set up. But request-time inference has real costs: latency, compute expense, reliability concerns, and a dependency on model-serving infrastructure that adds operational complexity.

Pre-computation trades flexibility for simplicity. You lose the ability to handle truly novel inputs, but you gain speed, reliability, and dramatically lower cost. For a surprisingly large number of features, that’s the right trade.

The questions I now ask early in any AI feature scoping: Is the underlying data static enough to pre-compute? Can the feature be decomposed into an offline understanding step and an online retrieval step? What’s the simplest architecture that delivers the right user experience?

For this project, the answers led to a sixty-second offline job, an 8MB index file, and a dot product. The app works, the results are good, and the monthly hosting cost is zero.

Sometimes the best AI architecture is the one where the AI already finished running before the user showed up. (Source code.)

Leave a comment