Sent from my ipod

Beyond Correlation Does Not Imply Causation

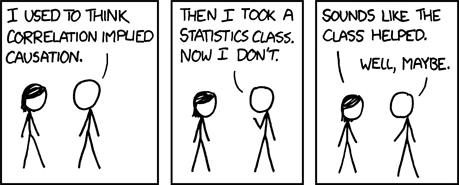

This is my favorite xkcd cartoon. I didn’t get it immediately. If you spend a little bit of time, the strip is funny because the guy is not sure if the statistics class caused him to understand that ‘correlation does not imply causation.’ It’s quite meta, but once you understand that correlation does not imply causation, you tend to be quite cynical about all the articles in media that imply causation. For example, an article may conclude that ‘Companies that invest in technology tend to be more profitable than those that do not.’ But what if the investment in technology is not what is making the company profitable? What if the companies that are more profitable also tend to invest in technology? Therefore, the investment in technology does not necessarily cause profits. Maybe it does, but there is no one test that proves this 100%. Once this piece of insight is deeply ingrained in you, you stop taking for granted the claims and studies conducted in labs behind closed doors. It’s important to question almost every single article making a claim of causation that doesn’t use a combination of techniques to convince you of the claim.

Averages and forces beyond measure

If you know what short selling a stock means, skip to the next paragraph. A common strategy that traders use if they know that a stock is about to tank, is to short sell the stock. In reality, this means borrowing a stock from a lender for the current price at time t, sell in the market for the current price at time t, wait for the stock to nose dive between the time t and t+1, buy the stock back at time t+1 and sell it in the market at time t+1. Therefore, you fake sold the stock in the market at a higher price and bought the stock at a lower price, making the difference in profit.

Since short selling involves borrowing a stock, which costs money, many traders look at buying (going long) negatively correlated (the stock will drop in price when the price in the other stock rises) stocks instead. A lot of inexperienced traders get dinged because they assume that the stocks are negatively correlated and will stay negatively correlated during the time that their strategy is active. Primarily for two reasons:

Stock correlations are measured in averages over time. Traders usually have a time horizon to execute and reverse their trades to bank profit. So once you introduce the time variable (also known as a confounding variable) the negative correlation may not hold true anymore in the trader’s time horizon.

To understand the second reason, it is worth questioning why the stocks are negatively correlated in the first place. This could be due to a combination factors. One of them is due to large institutions having strategies that automatically rebalance their portfolio in a way that results in selling some stocks, when they buy certain stocks. This makes the market look like the stocks are negatively correlated. This works well and the day traders can use this to their advantage, until the time it doesn’t. Until the time the large institution changes its strategy or replaces one of the two stocks. This is just one example. Add a number of other variables to this, and it becomes hard to measure all the forces that impact this correlation.

Can you prove that correlation is due to causation?

The short answer is no but we can get comfortably close, depending on the business situation :

A/B hypothesis testing with extreme sampling

It’s quite a standard technique to take a wide variety of samples and run them through an A/B hypothesis test. It’s a relatively cheap mechanism to prove that your correlation hypothesis is indeed true. This is often done in web experiments to measure conversions, where a certain audience (Audience A) is exposed to a change and the remaining audience (Audience B) is not. The trick is to avoid as much homophily as possible within a certain audience group. In reality, this would be quite hard to avoid and one solution is to assign the audience split using a perfect randomizer (i.e. extreme sampling).

Eliminate the ‘B causes A’ and bidirectional fallacy

When you observe that two entities are correlated and conclude that entity A causes entity B, it is also important to eliminate the other two causations. First, that entity B doesn’t cause entity A and second the causation is not bidirectional. For example, when one concludes that wind causes windmills to rotate faster, it is important to eliminate the possibility that a fast rotating windmill causes more wind. Also, we should eliminate the bi-directional causation aspect by highlighting that the wind is caused by the difference in heating temperatures over land vs water.

Eliminate all possibilities of business knowledge

An obvious way of eliminating correlations is to simply use experience over observations in data. Although, many managers of our generation take this too far. So it is important to reason why a causation is impossible when you see a correlation in the data. Here is an extreme example : There is correlation in data between the rise in ice cream sales and the high cases of drowning. This obviously makes no sense. The missing variable that the correlation doesn’t talk about is that these both occurrences happen only in the summer. It is natural that high weather temperatures cause ice cream sales to go up. Similarly with higher temperatures make more people go out swimming in open waters, causing more number of drowning related accidents.

Granger’s causality test

The Granger’s test is a little harder to implement. The basics of Granger’s causality test is to have enough experiments that will predict the future outcome of a time series based on past values on the time series. You can of course choose to run the experiment by back testing with data. Assuming it is time t now, you can use time t-2 to predict values at time t-1. In fact, this is a standard method used in predictive modeling to measure the predictive strength of a certain model - also known as holdout testing.

Causal Modelling

Even after performing all these tests, you can still be never a 100% sure that correlation does imply causation, but the good news is for a lot of the problems we face in business today we don’t require a 100% confidence.

It is up to the person making the claim to weigh the trade-off of increasing investment to reduce the assumptions made versus deciding that the conclusions are good enough given the assumptions.

There is a lot more theory around correlation and causation, but hopefully the next time you read an article that is making a causation claim, I hope you’ll be more cynical and ask for more backing of the claim instead of a lame correlation.